After years of travel, research, and writing, I’m thrilled to share that my first book, Shattered Lands, is finally out in the world.

This book traces the unraveling of the Indian Empire and in true Travelsofsamwise style, it opens with the British Empire’s first attempt to contact aliens. I hope you enjoy it!

Introduction

You can’t actually see the Great Wall of China from space. It’s a myth. Even if you were to squint your eyes while peering down at earth from the International Space Station you would not be able to see it.

But the border wall dividing India from Pakistan is unmistakable.

For more than three thousand kilometres, from the Arabian Sea to the icecaps of Kashmir, a line intended to divide Hindus from Muslims is visibly etched onto the surface of the globe. Three layers of fencing, three and a half metres high, are accompanied by 150,000 floodlights, thermal vision sensors and rows of landmines.1

This wall has, for the most part, rendered Indians and Pakistanis completely inaccessible to one another, and one of the only times that they can interact without going abroad is to attend a ceremony at the Wagah border post. Here, every evening at sunset, two national flags are lowered, and the turbaned border security forces of either country proceed to aggressively goose-step at one another in a jingoistic pantomime that wouldn’t be out of place in Monty Python. ‘Long Live India,’ cries the crowd from one side. ‘Long Live Pakistan,’ cries the other.

The India–Pakistan border isn’t the only heavily armed frontier in the region. Today South Asia is one of the most fortified, fenced and landmined zones on the planet. The barrier dividing Bangladesh from India, for example, is the longest in the world, fitted with thermal-imaging sensors and guarded by drones via a satellite-signal command system. Sixteen hundred kilometres of fencing is currently being built to divide India from Burma.2

Yet astonishingly, a century ago, none of these borders existed.

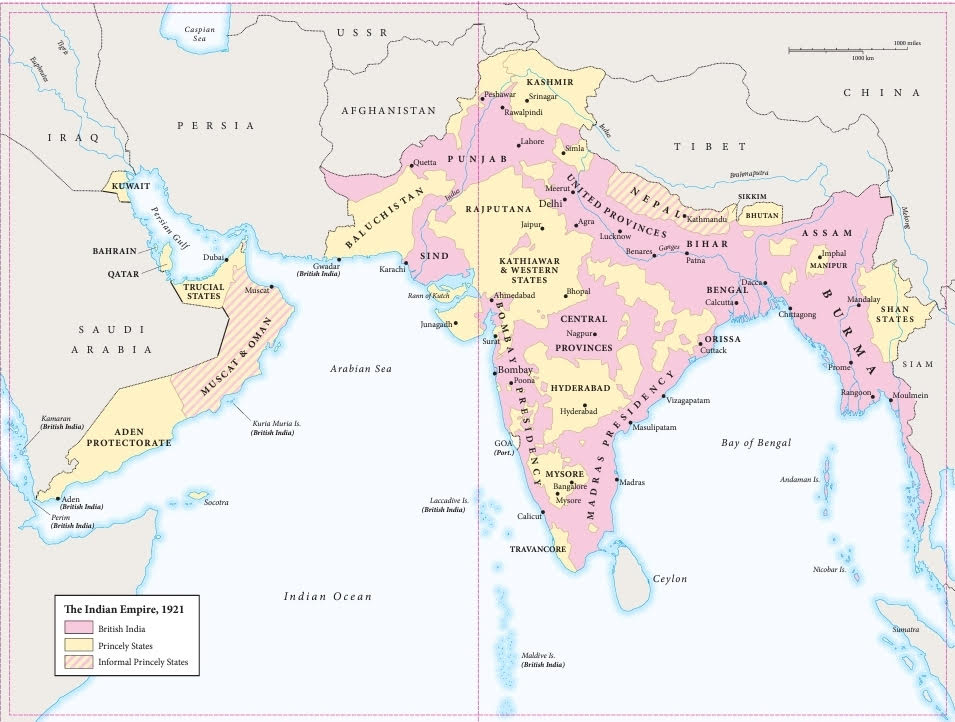

As recently as 1928, a vast swathe of Asia — India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, Bhutan, Yemen, Oman, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait — were bound together under a single imperial banner, an entity known officially as the Indian Empire, or more simply as the Raj. It was the British Empire’s crown jewel, a vast dominion stretching from the Red Sea to the jungles of Southeast Asia, home to a quarter of the world’s population and encompassing the largest Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities on the planet. Its people used the Indian rupee, were issued passports stamped ‘Indian Empire’, and were guarded by armies garrisoned forts from the Bab el-Mandab to the Himalayas.3

And then, in the space of just fifty years, the Indian Empire shattered. Five partitions tore it apart, carving out new nations, redrawing maps, and leaving behind a legacy of war, exile, and division.

At the start of 1928, however, few could have imagined how rapidly the Indian Empire would unravel. To most, the Raj still seemed an unshakable force, its dominion stretching across continents. Indeed on the first day of that year, as snow, sleet and rain showered down onto the streets of London, the British Empire tried for the very first time to contact extraterrestrial life.4

It had been a decade since the end of the Great War, and Britain was now a country firmly looking towards its future. Aeroplanes were flying over the Atlantic Ocean and there was concern about a new phenomenon called ‘traffic.’5 The British Empire was at its zenith and now it prepared to reach into space as well. Britain’s new public radio service, the BBC, had been founded a few year earlier, and as tens of thousands of people tuned in that morning, they could make out the voice of a man with a clipped London drawl. ‘Hullo all stars and nebulae,’ he began. ‘A greeting to all friendly planets circling with us on the everlasting tour.’ Have ‘our waves’ reached you yet?

A pause followed as the broadcaster waited for an answer to arrive from the stars, but none was forthcoming. ‘Reply if you please,’ he entreated, but again silence ensued. ‘London’s Message to Mars: No Reply Received’ was the main headline on newspaper stands that week.6

Instead of speaking to aliens, therefore, the BBC presenter changed tack and turned to address the people of the British Empire, from London to Toronto and from Cape Town to Calcutta. As well as addressing ‘the colonies’ more generally, a message from King George V was specifically directed to ‘the people of India’, who represented four-fifths of the British Empire and a quarter of the world’s total population. ‘I reciprocate your earnest hopes,’ the king told his Indian subjects, ‘that 1928 may be the dawn of a new era of peace, happiness and prosperity to you all.’7

The ‘India’ he was addressing was almost twice as large as modern India, yet today, its scale has been largely forgotten; few books acknowledge its reach into present-day Yemen, Dubai, Burma or Nepal.8 Even at the time, Britain played down the size of the Indian Empire for diplomatic reasons, and maps depicting the Indian Empire in its entirety were only published in top secrecy.9 The Viceroy’s informal protectorates over Nepal and Oman were never officially recognised as such, and the Himalayan states which bordered China’s dependency of Tibet were coloured red on Indian Imperial maps for only ten years (1897–1906). Similarly the Arab states bordering the Ottoman Empire were usually left off Imperial maps altogether, to avoid aggravating Constantinople.10

Nonetheless, these protectorates were all legally part of ‘India’ under the Interpretation Act of 1889. They were run by the Indian Political Service, defended by the Indian Army, and subservient to the Viceroy of India. The standard list of princely states even opened alphabetically with Abu Dhabi, and the Viceroy Lord Curzon himself argued that Oman should be considered “as much a Native State of the Indian Empire as Lus Beyla or Kelat.”11 The absence of these states from British maps was much remarked upon at the time, and a lecturer to the Royal Asian Society even joked that

“As a jealous sheikh veils his favourite wife, so the British authorities shroud conditions in the Arab states in such thick mystery that ill-disposed propagandists might almost be excused for thinking that something dreadful is going on there.”12

In fact, protectorates such as these constituted almost a third of the Indian Empire: Britain never ruled over all of modern-day India and from Jaipur to Hyderabad, six hundred thousand square miles of the Indian Empire’s territory were controlled by monarchs who had given up their foreign policy and defence to the British Viceroy of India, but were otherwise independent.13 These states could vary wildly from minute principalities to considerable countries in their own right: Kashmir was larger than France, Travancore’s population was greater than Austria’s, and Hyderabad’s economy was a similar size to Belgium’s.14

The Maharajas, Sheikhs and Nizams who ruled these kingdoms were often fabulously wealthy figures. After the death of J. D. Rockefeller in 1937, TIME magazine named the Nizam of Hyderabad the richest man in the world and the fifth richest in history. British administrators and Indian nationalists frequently dismissed these princes as absurd feudal rulers with an average of ‘11 titles, 5.8 wives, 12.6 children, 9.2 elephants shot, 2.8 private railway cars, 3.4 Rolls Royce’s, and 22.9 tigers killed’ between them.15 Yet the princes were so much more than this. The Maharaja of Mysore was a celebrated philosopher whose state modernised faster than many British-ruled territories, and the Nawab of Rampur built up the most extensive library in Asia. After the fall of the Ottoman Caliphate, the Nizam of Hyderabad was arguably the world’s foremost Muslim ruler and his capital the most prominent city of Muslim learning outside the Arab world.

All the lands within the Raj had been connected by trade, marriage, and faith long before the British had ever arrived, and until the twentieth century, even religious boundaries in the region were fluid. For large swathes of the Indian Empire, devotion to multiple faiths at once was seen as no more contradictory than subscribing to both religion and science. Punjabi Hindu Khatris traditionally raised their eldest son as a Sikh, whilst in Kerala the Virgin Mary was sometimes worshipped as the sister of the Goddess Bhagavati.16

Then, with the First World War, everything changed.

By 1919 the war effort cost the Indian Empire nearly £146.2 million – £14 billion today – and more than a million Indian soldiers fought overseas during the war, only to return home to find their country unchanged, their rights denied.17 White-only clubs still dotted the subcontinent, and while incremental reforms granted Indian politicians token positions at the provincial level, true power remained in British hands. The Indian Empire generated vast wealth, yet Indians had little say in how it was spent.

Indian nationalists, emboldened by increasing anti-colonial rhetoric, subsequently began to press harder for self-determination. Then, in 1919, British Indian troops under General Dyer marched into a walled garden in Amritsar, blocked the only exit, and opened fire on unarmed protesters. Hundreds were killed, perhaps over a thousand. For many Indians, the massacre marked a turning point—proof that the Government of British India would never reform itself, only repress.

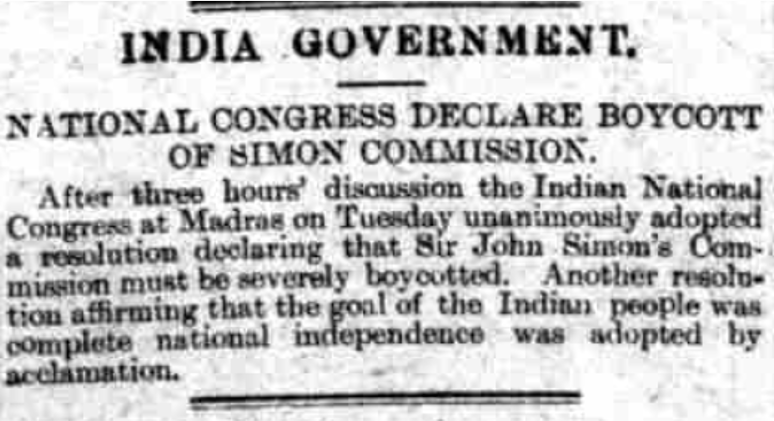

And so, even as the BBC spoke of Britain reaching the stars, opposition to British rule was hardening on the ground. That very day, as the Taunton Courier reported on the Empire’s attempt to talk to aliens, another story appeared beside a column on the mysterious death of three hundred pigeons. India’s largest political party, the Indian National Congress, had recently voted to affirm ‘the goal of … complete national independence.’18

The nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehru had proposed the motion in Madras, the capital of India’s humid south.19 He did this because the British government was planning to write a new constitution for their Indian colony, and the Simon Commission, formed to suggest reforms, had not included even a single Indian on its committee. In fact, most of the commissioners had never been east of Paris, yet they would now be answering the most pressing questions in India’s modern history. What was India? Who counted as Indian? And the most important question of all – should the Indian Empire be Partitioned?20

Demands for ‘independence’ were widespread, and that year no one could have suspected that day that the nations of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Yemen and Burma would soon emerge from the wreckage of British India. Nor would anyone have imagined that tiny princely states like Bhutan and Dubai would last until the end of the century while massive states like Hyderabad would not. Many of these countries have retrospectively written their histories back into the ancient past. But as late as 1928, not one of the borders that later sliced through South Asia was foreseen.

This book tells, for the first time, one of the great epics of the twentieth century: the extraordinary story of how five partitions transformed Britain’s Indian Empire into twelve nation states.

The shattering of the Indian Empire began in 1937, when the first largely forgotten partition carved Burma out from India to fulfil a decades-old demand by the ethnic Bamar community, as well as the desire of Hindu nationalists for ‘India’ to match the boundaries of the ancient Hindu holy land ‘Bharat’. The results would be devastating, triggering famine, a catastrophic migration crisis, and laying the seeds for several insurgencies.

A second partition – the partition of the Arabian Peninsula from India – began the same year with the separation of Aden, and would be completed a decade later with the transfer of the Persian Gulf states in April 1947. Were it not for this separation, most of the Arabian Peninsula except for Saudi Arabia might have become part of India or Pakistan after independence. But instead, the states of the Gulf would be the only princely monarchies except for Nepal and Bhutan to survive intact into the twenty-first century.

In 1947 tensions between India’s majority Hindu community and the enormous Muslim minority culminated in what might be called the ‘Great Partition’21 of British India, and the creation of Pakistan out of the Muslim majority districts in the east and west of the subcontinent. As the country was torn apart, India descended into violence on an epic scale, precipitating the largest forced migration in human history. Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal has called it ‘the central historical event in twentieth-century South Asia,’ one that continues to inform how a quarter of the world ‘envisage their past, present and future’.22

A fourth partition – the Partition of Princely India – occurred the same year. Much of the shape of modern India, Pakistan and Burma was actually determined by the decisions of the Indian princes, rather than British administrators, who chose to ‘integrate’ their kingdoms with one of the new countries, or become independent. Integration mostly took place along religious lines, with Muslim kingdoms integrating with Pakistan, Buddhist ones with Burma and so on. Yet several large kingdoms broke with this trend, and the massive and overwhelmingly Hindu Jodhpur State very nearly joined Pakistan rather than India. The decisions of these princes would determine over half of the India–Pakistan border – more than 80 per cent if we exclude modern Bangladesh.

Finally, twenty-four years later in 1971, the fledgling nation of Pakistan was itself torn apart, this time by civil war, and after a fifth and final partition, East Pakistan gained independence as Bangladesh. South Asia’s youngest nation was born and India became the region’s undisputed power. The same year, the British abolished their protectorates over the Gulf states: the last of India’s princely states to gain complete independence from imperial rule.

Each of these Five Partitions were linked, influencing the next like a set of dominos, and in ways that are often overlooked today. Standard Indian histories often describe ‘Undivided India’—roughly modern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—as a timeless entity, later divided by British policies and Muslim nationalist demands. In reality, this ‘Undivided India’ was itself a colonial construct, existing only for five months in 1947 following the overlooked partitions of Burma and Arabia. Hindu nationalism was a key driving force in these earlier partitions, envisaging an independent India that resembled the ancient Hindu holy land of Bharat including neither Burma or Arabia. As we shall see, the Arabian and Burmese frontiers of the Raj were once central to the very idea of India, and several of the founding fathers of Yemen and Burma had even once conceived of themselves as Indian nationalists. As late as the 1920s, the nationalist campaigns of Gandhi and Jinnah had as much of an impact there as anywhere else.

India is not the only country in the region to ignore its complex past. In the decades since 1971, nationalist historians of each of the Raj’s successor states have argued that their countries were inevitable. Bangladeshi nationalists, for example, often claim that Bengali Muslims were always fated to form their own nation state and Burmese nationalists often refer to a ‘separation’ from India, rather than a partition, despite the numerous communities who were divided from one another as a result. Many nationalists from former protectorates of the Indian Empire such as Nepal and the UAE even claim that they were always independent, and ignore the former place in the Indian Empire entirely. This book, on the contrary, shows that as late as the 1920s, none of the nation states we see today – from Burma to India to Kuwait – were inevitable.

Even as new borders were being drawn, people assumed that cross-border relationships and trade would continue as before. For more than two millennia, South Asian communities and their cultures had spread out across Asia into China, Afghanistan and Arabia, and from East Africa to South-East Asia. As European empires were torn apart in the twentieth century, these ancient social and commercial links could have been rekindled. But instead new national identities only hardened. Countless communities found themselves on the wrong side of new borders, leaving a series of suppurating wounds that continue to bleed into the present.

The collapse of the Indian Empire has remarkably never been told as a single story. With every division archives were scattered across twelve nation states – thirteen if we include Britain. Subsequent divisions between the ‘Middle East’, ‘South Asia’ and ‘South-East Asia’ crystallised after the Second World War. Each Partition is now studied by a different group of scholars and the ties that once linked a quarter of the world lie forgotten. In 2011 Burmese author Thant Myint-U wrote:

Almost no one I knew in Delhi had ever been to Burma, and ... I was told there are no Burmese-speaking experts in India. Instead, there were hints of a slightly forlorn connection: a relative who had been born in Burma, a recipe that had been kept in the family after a time spent long ago in Rangoon, a sense of old religious or cultural affinity, an interest, but otherwise little knowledge.23

Thanks to revolution and social upheaval, the history of the Indian Empire sank into the depths of numerous national archives. In this way, separated by international and academic borders, one incredible tale has itself been partitioned into several very different narratives.

This book, for the first time, presents the whole story of how the Indian Empire was unmade. How a single, sprawling dominion became twelve modern nations. How maps were redrawn in boardrooms and on battlefields, by politicians in London and revolutionaries in Delhi, by kings in remote palaces and soldiers in trenches.

It is a history of ambition and betrayal, of forgotten wars and unlikely alliances, of borders carved with ink and fire. And, above all, it is the story of how the map of modern Asia was made.

Saddiki, S., World of Walls: The Structure, Roles and Effectiveness of Separation Barriers (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2017) p51

Marshall, T., Divided: Why We’re Living in an Age of Walls (London: Elliot & Thompson, 2018) Chapter 5; Saddiki, S., ‘Fencing the Desert: Contexts and Politics of the Gulf Border Walls’, Journal of Borderlands Studies. 2023

Everyone in British India was entitled to an Indian passport – including in Aden and British Burma – and the rupee was used across the territory. Things were a bit more complicated in the patchwork of Princely States, where people were treated as ‘British Protected Persons’ rather than ‘British Subjects’. The British accepted certain state passports and other certificates of identity, such as those issued from Bahrain or Muscat, but these would only be valid when stamped by a Government of India Political Agent. See QDL IOR/L/PS/12/1461 “Aden Protectorate Boundaries: Inclusion of the Hadhramaut”: p69-76; IOR/R/20/A/3397: National Status of Natives of the Hadhramaut; Onley, J., The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Blythe, R., The Empire of the Raj: India, Eastern Africa and the Middle East, 1858–1947 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2003).

Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 4 January 1928

Weekly Dispatch (London), 1 January 1928

Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 4 January 1928; Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 4 January 1928; Western Daily Press, 2 January 1928

Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 4 January 1928

The modern Republic of India has an area of approximately 3,287,000km2. By contrast, the Raj was closer to 4,900,000 km2 . See Onley, J., “The Raj Reconsidered: British India’s Informal Empire and Spheres if Influence in Asia and Africa”, in Asian Affairs, 40:1, p.54.

QDL, IOR/L/PS/20/C91/1 “Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf.” Lorimer’s Gazetteer of Arabia used the same 32-miles-to-the-inch scale as the Imperial Gazetteer of India, so that the Arabian Map could be “‘fitted alongside the map of India, thus giving, at a glance, a map of that portion of the world between Burma and Egypt’. Yet whilst the Gazetteer’s of India were publicly available, the Arabian ones were top secret and only made available a decade after Indian Independence. See Lowe, D. A., “Colonial Knowledge: Lorimer’s Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia” in Qatar Digital Library <https://www.qdl.qa/en/colonial-knowledge-lorimer’s-gazetteer-persian-gulf-oman-and-central-arabia>.

Onley, J., The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

The Indian Civil and Political Services had a larger presence in the Persian Gulf than in todays Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Mizoram. See Onley, J., “The Raj Reconsidered: British India’s Informal Empire and Spheres if Influence In Asia And Africa”, in Asian Affairs, 40:1, p.54

Rich, P., Creating the Arabian Gulf: The British Raj and the Invasions of the Gulf (Lexington Books: Plymouth, 2009) p84

There various legal distinctions between different types of suzerainty that the viceroy exercised over states. Some states were labelled ‘protectorates’ and some were labelled ‘protected states’. Some states such as Nepal and the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman never signed an exclusivity agreement and also had treaties confirming their legal independence. Nonetheless, they were completely dependent on India and indirectly ruled by the Viceroy through a ‘residency’ in precisely the same way as the other states. James Onley has show, there was virtually no practical difference between the two on the ground. The very title 'Sultan' was actually given to the Sultans of Oman by the Government of India and were subsequently schooled at Mayo College in Rajasthan, along with the other Maharajas, and even appeared at the Delhi Durbars. Oman adopted the Rupee and, when threatened, it was the Indian army that would come to the Sultanate's protection. Contrary to popular perception, the Viceroy’s indirect rule over states like Kashmir or Jaipur was more or less identical to the rule exerted over states like Oman and Dubai, and the terms ‘princely state’ and ‘native state’ were frequently applied to both. See Onley, J., The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007)

Copland, I, The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire 1917-1947 (Cambridge University Press: 1997) p8

Pillai, M. S., The Ivory Throne (HarperCollins India, 2015) p461

https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2008/jun/28/india

Das, S., India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images and Songs (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018) p11; https://www.india1914.com/Price_of_war.aspx#:~:text=India's%20Financial%20Contribution,to%20around%20%C2%A314%20billion.

Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 4 January 1928

Kozicki, R., India and Burma 1937–1957: A Study in International Relations (PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1959) p90

The word ‘Separation’, rather than ‘Partition’ is mostly used at the time. However the word ‘Partition’ would come to be used for the separation in the course of the 1930s, adopted by figures such as Gandhi and Ambedkar.

This term comes from Yasmin Khan’s eponymous book, and here I will be using it more specifically for the 1947 Partition of British India.

Dalrymple, W., ‘The Great Divide: The Violent Legacy of Indian Partition’, New Yorker, 22 June 2015, newyorker.com/magazine/2015/06/29/the-great-divide-books-dalrymple

Myint-U, T., Where China Meets India: Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018) p246

I worked in the Middle East in the early 2000s where an older age person still referred to currency as “Rupiya” even though the official currency was Dinar! On speaking further learnt for the first time that during his childhood they used the Indian rupee! As someone from India, I had never read or heard about it.

Looking forward to devouring this book!

The work looks groundbreaking and outstanding. When available in the US I will certainly order a copy. Just curious why is Sri Lanka not considered part of the Raj? I lived there for two years. My British friends thought that older Sri Lankans were very, for a lack of a better word, British.