If you’re wandering the Midlands and happen to take a wrong turn off the A38, you might just find yourself staring at a spectacular gothic cathedral that looks more at home in Chartres or Cologne than Staffordshire.

Rising from the sleepy market town of Lichfield, its three spires - whimsically nicknamed the ladies of the vale - pierce the skyline.

Lichfield Cathedral is England's only three-spired medieval cathedral, and perhaps its most under-sung masterpiece.

This cathedral has seen plagues and purges, revolutions and restorations. It housed the bones of St Chad, was battered in the Civil War, and once had its spire shot clean off by Parliamentary cannon fire.

The 14th century cathedral is also home to the Lichfield Gospels - a gorgeously illuminated manuscript that contains some of the earliest known examples of old Welsh. Made before the book of Kells but after Lisdisfarne, it is basically one of the best early British manuscripts to survive to today.

Lichfield Cathedral is not just a relic of the Middle Ages, however.

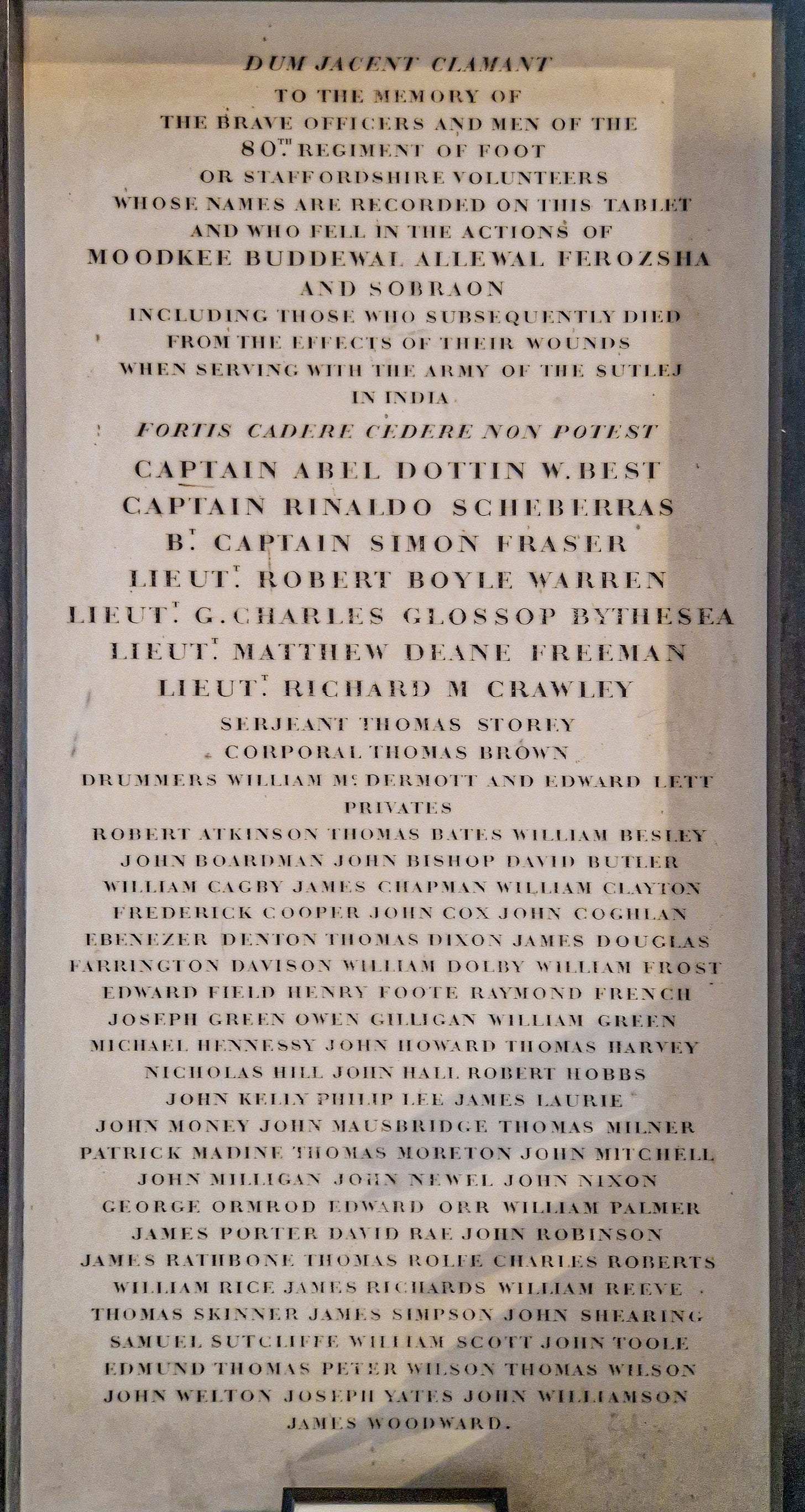

So so many of Britain's cathedrals and parish churches, Lichfield's walls hold the memorials of soldiers, missionaries, and administrators who served and died in the far-flung corners of the British Empire.

Indeed tucked among its Gothic arches and misericords is a monument to the Sutlej Campaign, which saw the annexation of Punjab.

And until recently, hanging above it were the Sikh standards of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Empire.

This is their story.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

On December 4, 1846, the British troopship Madagascar anchored at Gravesend, her decks lined with weary soldiers.

They had spent three months at sea, sailing from Calcutta through storms and sickness, and as they disembarked, the crowd outside spotted five battle flags of the Sikh Khalsa fluttering in the winter wind.

Torn by cannon fire and soaked in the dust of Punjabi battlefields, these captured colours had been seized in the fiercest engagements of the First Anglo-Sikh War: one at Ferozeshah, two at Aliwal, and two at Sobraon. To the British public, they were symbols of a new imperial dominance.

Two days later, as the regiment marched into Chatham Garrison, they were met with fanfare: the band of the Royal Marines struck up God Save the Queen, and thousands lined the streets, cheering the return of those who had “subdued the Sikhs.”

A British poet in the crowd declared at the sight of the troops:

At last they tread their native shore;

True warriors- humane as brave-

Who firmly stood when false Lahore

Proudly their tatter’d banners wave-

Rent into rags by shot and shell;

Proud is the bayonet and the glaive

Which could defend their flags so well.

The Road to War

Behind the pageantry and patriotic verse lay the story of a powerful Indian kingdom crumbling from within, of a brave but divided army, of betrayal, resistance, and the relentless advance of empire.

The First Anglo-Sikh War had begun just a year earlier, in December 1845, on the windswept banks of the Sutlej River.

The river Sutlej, since 1809, had acted as a border dividing the British protected chiefdoms of Punjab on the east bank and the mighty Sikh Empire founded by Maharaja Ranjit Singh on the west.

Throughout Ranjit Singh's lifetime, the two powers on either side of the river held each other in cautious respect. Ranjit Singh had kept the British at bay during his lifetime through shrewd diplomacy and sheer strength.

But after his death in 1839, his empire descended into chaos. The Lahore court became a theatre of assassinations, power struggles, and palace intrigue. Four maharajas rose and fell within six years. Real power shifted to the Khalsa Army, a vast and disciplined military force that had grown independent and restless.

At the centre of this maelstrom was Maharani Jind Kaur, Ranjit Singh’s last queen and the mother of the boy-king Duleep Singh. Acting as regent, she struggled to hold the kingdom together while surrounded by courtiers who distrusted her and generals who ignored her.

The British, meanwhile, had stationed troops near the Sutlej and were watching with growing interest. In the ensuing political chaos, the Khalsa believed an invasion was imminent.

Rather than wait, they crossed the river into British territory, hoping to seize the initiative. This was the breach of the 1809 Treaty the British had signed with Ranjit Singh, where they promised each other that they would respect their borders. This was the perfect excuse the British needed, and a war officially broke out between the Sikhs and the British.

A Bloody Campaign

The first major clash came swiftly on the plains of Mudki on December 18, 1845. The British, under the command of Sir Hugh Gough, met the Sikh forces led by Lahaur Singh. The fighting was fierce and chaotic; the Sikh artillery and cavalry charged relentlessly, forcing the British into a costly defensive stand. British regiments, including the battle-hardened 31st Regiment of Foot, were nearly overwhelmed by the ferocity and discipline of the Khalsa troops. Despite heavy casualties, the British held the field, but the victory came at a steep price.

Barely a week later, from December 21 to 22, the armies met again at Ferozeshah, near the Sutlej. This battle would become infamous for its brutality and confusion. The Sikhs, under generals Tej Singh and Ranjodh Singh, entrenched themselves in strong defensive positions and poured devastating fire on the advancing British.

British forces, exhausted and battered, suffered severe losses and found themselves in danger of collapse. It was only after a desperate night of fighting and confusion, exacerbated by delayed reinforcements and the suspicious withdrawal of Sikh troops under General Tej Singh, that the British managed to rally and force the Sikhs to retreat. The true reasons for the Sikh commanders’ inconsistent conduct would haunt the war’s reputation.

By January 28, 1846, the British regrouped and struck at Aliwal, where General Harry Smith commanded a decisive assault against Sikh forces led by Ranjodh Singh. The British cavalry, disciplined and coordinated, broke through Sikh lines, capturing two more of the coveted battle flags. This victory boosted British morale and turned the tide of the war in their favour.

The campaign culminated in the battle of Sobraon on February 10, 1846, the war’s most decisive and devastating confrontation. The Sikhs, commanded by Tej Singh and Ranjodh Singh, fortified their position on the eastern bank of the Sutlej, building a defensive barricade anchored by the river. British forces, under Gough and Smith, launched a fierce artillery bombardment that shattered Sikh defenses.

As the battle turned against them, the Sikh troops attempted to retreat across a narrow, heavily congested bridge spanning the Sutlej. Panic set in, the bridge collapsed under the weight of fleeing soldiers, and British artillery and musket fire tore into the trapped masses. Thousands of Sikh soldiers drowned or were cut down in what became a massacre. Two more battle flags were captured amid the chaos, symbols of a shattered resistance.

Yet, despite the ferocity and apparent completeness of British victory, the war’s outcome was shaped by more than sheer military force. Rumours and evidence of treachery and betrayal within the Sikh command deeply stained the Khalsa’s efforts. Key generals, including Tej Singh and Lahaur Singh, were accused of deliberately withholding troops or retreating at crucial moments, possibly colluding with the British to preserve their own power. This internal division critically undermined the Sikh war effort and demoralised their soldiers.

The Fall of a Kingdom

The war ended with the Treaty of Lahore in March 1846. The terms imposed by the victorious Britons were unforgiving. The proud Sikh Empire was forced to relinquish vast territories, particularly all lands between the Beas and Sutlej rivers, along with the whole of Kashmir, to the British East India Company.

It was also forced to relinquish the kohinoor diamond.

The empire that once stood as a sovereign and powerful force in northern India was now reduced to a fragile shadow of itself.

In Lahore, the heart of the empire, the British installed a Resident, Sir Henry Lawrence, whose presence was a constant reminder that real power no longer rested with the Maharaja. The young Maharaja Duleep Singh, barely seven years old at the time, remained on the throne, but only in name, puppeted by the Resident.

At the center of this loss stood Maharani Jind Kaur, the fiery widow of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and mother to the young ruler. Known for her political savvy, fierce independence, and refusal to bow to British demands, Jind Kaur was the last true voice of Sikh resistance in a now subdued court.

As regent, she had fought to preserve her son's independence, but the British viewed her as a threat. By 1847, she was stripped of her power, placed under house arrest in the Sheikhupura Fort, cruelly separating her from her young son, Duleep Singh.

From Sutlej to Gravesend

When the 31st Regiment returned to Britain in December 1846, trailing five captured Sikh colours through the streets of England, they carried home as symbols of the dawn of a new imperial order, the Sikh battle flags, stained by the sweat and blood of countless warriors, stood as the final emblems of a once-mighty empire brought low.

Yet the story was far from over. Though the First Anglo-Sikh War had shattered the Sikh Empire, it had not yet been fully conquered. Within three years of the First Anglo Sikh War, simmering tensions would ignite again in the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848–49. This brutal conflict would seal Punjab’s fate, folding it entirely into the British Empire, which would result in its annexation in 1849.

In the years that followed the annexation, the young Maharaja Duleep Singh was taken from his homeland, transported to England, and baptized into Christianity, transformed into Queen Victoria’s “Black Prince of Perthshire,” a living trophy of imperial conquest, much like the torn flags of his erstwhile kingdom.

Meanwhile, Maharani Jind Kaur, the indomitable Queen Mother, escaped imprisonment to seek refuge in Nepal, where she would live in exile, a political refugee far from the kingdom she once fought to protect.

That cold December day in 1846, as the torn flags fluttered before cheering crowds at Gravesend, they stood as proud trophies of the empire.

For visitors in 2025, the monuments of Lichfield Cathedral remain a vivid portal into Britain’s imperial past, preserved in the solemn halls of the church.

But for Punjabis and Sikhs who come to see them, these flags carry a far deeper meaning, a silent witness to a kingdom lost, and a culture subdued.

Great article.

In Lahore, we have Lawrence Gardens (now known as Bagh-e-Jinnah). It was named after John Lawrence, Henry's brother.

You may be interested in this review I wrote of your dad’s book. I’ve also reviewed The Anarchy.

Look forward to reading your book too :)

https://kabiraltaf.substack.com/p/review-william-dalrymples-return